As you probably know from reading the last few weeks of posts, my family (Husband and Child) has been in the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) for just over two years now. This branch of Anglicanism has three "streams" that intertwine like a braid to form a unique experience and theological "tent." A few weeks ago, I wrote a post exploring the Anglo-Catholic stream, and one on the Reformed or Protestant stream. This week, I'd like to explore the third stream, Holiness or Pentecostal. As a disclaimer, this is the stream I know least about from personal experience, though not by much.

Review of Anglicanism

Two key aspects of Anglican prayer and practice are adherence to the 39 Articles of Religion and use of the Book of Common Prayer in individual, family, small group, and congregational devotions and worship. Past posts link to both resources, which are available in full text online.

Why are these two so important? First, the 39 Articles combines both orthodoxy and breadth of acceptable doctrine, by limiting what must be believed, taught, and confessed by priests and laity to doctrines that have been (mostly) agreed upon since the first generation of the Church. Second, the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) ensures a standard text (rubric) so that no matter which Anglican congregation one worships in, s/he can be assured of knowing the order of service and that the words will not be taken liberties with.

The 39 Articles and the Holiness/Charismatic Stream

Do these two things fit togther? Opinion-wise, it depends on whom you ask (e.g., Les Fairfield says yes while Chuck Collins of VirtueOnline says no). Based on those sources and my background reading on each of the streams as well as Anglicanism itself, I do see room if nuance is allowed and hyperfocus on the stream isn't.

John Wesley has been named as the "point person" of how the stream originated. He preached heavily on (1) the ongoing work of the Holy Spirit in changing one's thoughts, words, and actions to conform more to the pattern of Christ, along with (2) experientialism.

Point (1) is also known as sanctification, in its broader sense (not narrowly defined as by some traditions). Where is sanctification in the Articles?

- Article 5, on the Holy Spirit: "The Holy Ghost, proceeding from the Father and the Son, is of one substance, majesty, and glory, with the Father and the Son, very and eternal God."

- Article 16, on sin after baptism: "Not every deadly sin willingly committed after Baptism is sin against the Holy Ghost, and unpardonable. Wherefore the grant of repentance is not to be denied to such as fall into sin after Baptism. After we have received the Holy Ghost, we may depart from grace given, and fall into sin, and by the grace of God we may arise again, and amend our lives. And therefore they are to be condemned, which say, they can no more sin as long as they live here, or deny the place of forgiveness to such as truly repent."

- Article 27, on Baptism itself: "Baptism is not only a sign of profession, and mark of difference, whereby Christian men are discerned from others that be not christened, but it is also a sign of Regeneration or New-Birth, whereby, as by an instrument, they that receive Baptism rightly are grafted into the Church; the promises of the forgiveness of sin, and of our adoption to be the sons of God by the Holy Ghost, are visibly signed and sealed, Faith is confirmed, and Grace increased by virtue of prayer unto God.

The Baptism of young Children is in any wise to be retained in the Church, as most agreeable with the institution of Christ."

While sanctification is not directly mentioned anywhere in the Articles, my reading sees it most in Article 16. The process of living as a child of God, in His family, begun at the moment of salvation (typically occurring in Baptism--the adoption proceedings of God) contines throughout one's life. It is not (as Platonists would say) the soul's journey toward God, but rather the body-and-soul walking with God and keeping the image He has placed within each Christian.

The BCP and Selection of Music

According to the guidelines and rubrics in the Book of Common Prayer, particular pieces of music (whether songs, hymns, or other) are not prescribed for individual congregations. Thus, music selection is up to the discretion of servant leaders in each congregation, reflecting such things as liturgical sensitivity, cultural awareness, and ability to lead congregants in learning new music.

To this end, I've found Phillip Magness' pocket-sized Lexham Ministry Guide, Church Music for the Care of Souls, extremely useful for providing general principles to care for parishioners' souls through music, no matter what the denomination. What are some key things he recommends?

- Lyrics of substance--the Word drives music regardless of tune. This criterion rules out a large number of contemporary Christian music (CCM) songs and a medium number of hymns, depending on how the exegesis of the Word was done at the time. It also allows better (more singable) tunes to be substituted if the words are excellent but the tune is clunky.

- Singability should meet the congregation where it is and then elevate it, which can look significantly different depending on the culural makeup. This criterion encourages periodic challenge and ongoing learning of new music. One aspect of my current congregation is its rather smaller set of hymns and songs compared to the 600+ hymns from the congregation I grew up in.

- Leaders should prepare enough to play/sing/lead well, not sloppily. This criterion doesn't require professional training for music leaders per se, but it does heavily emphasize adequate practice time so that timing and cues to the congregation are correct and (nearly) flawless.

- Participation should trump performance. Though leaders need to be in tune and have correct and consistent rhythm, congregants should not be expected to in order to participate in worship. Ideally, ongoing participation means ongoing mindful practice which means eventual skill and comfort level improvement for individual parishioners.

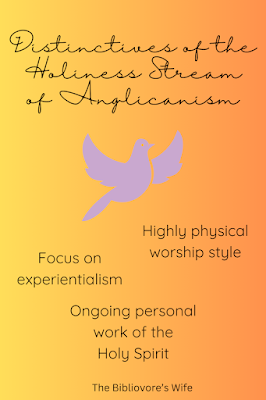

The Holiness/Charismatic Stream

This stream of Anglicanism has been around for a while, though as distinct theological movements the Holiness and Pentecostal movements have taken different forms. The way I see it, this stream brings balance to the other two.

Brief History

Here, I draw from Les Fairfield's essay linked above. The Church of England became a distinct entity in 1534 (situated just after the Protestant Reformation of 1517-??), although its breaking off from Roman Catholicism was not strictly for theological reasons. The Pentecostal/Holiness stream emerged about 200 years after the Protestant/Reformed stream did.

Fairfield pinpoints John Wesley's preaching in a context of surrounding Deism (God-as-watchmaker) as a possible starting point. Wesley observed ongoing improvement in moral character and actions in poor people's lives as a result of the indwelling Holy Spirit; this became a major emphasis of Methodism. (For context, the lead rector at our church came out of United Methodism; his tenure has provided a welcome contrast to the previous rector who, we were told, did not emphasize sanctification at all.)

The stream within Anglicanism was renewed during the charismatic renewal of the 1960s-1980s, which affected a number of different Christian traditions at different times. My parents were part of the Lutheran branch of the renewal for a few years.

What Charismatic-Focused ACNA Congregations Look Like

Particular descriptors for this stream include "enthusiasm," "charismatic," and "socially-focused." Let's define each of these according to its use in Anglicanism. "Enthusiasm" is used in the theological sense, which is very close to the Greek roots in denoting someone strongly and visibly possessed by God (or, for the Greeks, another deity). During the Reformation particularly, the term was used in a derogatory way to indicate that "enthusiasts" prioritized their perception of what the Spirit said over the written Scriptures.

"Charismatic" refers here to the continuationist position that (1) the named gifts of the Spirit continue to be given to believers in the present and (2) believers should pursue and responsibly use the gifts. More on this in a litle bit!

"Socially-focused" refers to John Wesley's emphasis on preaching to the poor because, from passages such as Isaiah 61:1, God still cares for them (as opposed to the views of the richest few percent of people who embraced Deism instead of full Christianity).

Synthesis: All Streams Together

Fairfield's quote toward the end of his essay sums up this topic nicely:

"Fellowship amongst the three historic strands of Anglicanism has often been difficult. Protestants initially abhorred the “ritualism” of the 19th century AngloCatholics. Both streams questioned the “enthusiasm” of the 20th century Pentecostal revival. But each stream has challenged the others in their weak points and their blind spots. The Protestant movement recalled the 16th century Church to the primacy of the Word—written, read, preached, inwardly digested. The 18th century Holiness movement reminded the Church of God’s love for the poor. The AngloCatholic movement re-grounded the Church in the sacramental life of worship. All three strands are grounded in the Gospel. Each one extrapolates the Gospel in a specific direction. No strand is dispensable. Other Christian bodies have often taken one strand to an extreme. By God’s grace the Anglican tradition has held the streams in creative tension. This miracle of unity is a treasure worth keeping."

Sources of Tension?

The main source of tension I see, especially in the young ACNA denomination, is that many members are not yet lifelong Anglicans, although many have come out of Episcopalianism. Therefore, they may not have experienced the unity of fellow Christians from all three streams working together in harmony. Anglicanism is a "big tent" theologically--some think too big--and so the set of core beliefs that all should hold is minimal. However, some streams may have problems with certain doctrines.

Recently, I read Andrew Wilson’s Spirit and Sacrament: An Invitation to Eucharismatic Worship. This brief paperback draws from an impressively wide range of readings, from Martyn Lloyd-Jones to Irenaeus. Wilson is a pastor of King's Church London, in the Evangelical Alliance and generally in the Reformed and Charismatic/Evangelical traditions.

Wilson speaks to the tension that juxtaposing Eucharistic (sacrament-focused, liturgical, tradition-rooted) and Charismatic (experientialist, charismatic) traditions and practices in the same congregations can bring. Charismatic individuals tend to be anti-"tradition" but do end up forming their own, younger, traditions. Eucharistic individuals tend to be anti-"innovation" which ends up including being either hard or soft cessationist. How can they get along?

Sources of Unity?

Wilson, in line with his thesis, speaks much more to this potential, though of course not directly about the ACNA's makeup. To echo Fairfield, the streams have the same focus on prayer and experiencing God's gifts as other streams but express this focus in different ways and different mini-directions.

One source of unity is the broader reach of combined 3 streams. Narrower theological and practical foci in a church body tend to attract smaller subgroups of people. A single, common liturgy--as noted in the Book of Common Prayer--is very helpful for reaching and discipling this broad audience. People become what they repeat.

Wilson makes the case for all Christians to thank God for, steward, and pursue the spiritual gifts with several quotes, based on the premise that all Christian theology begins with the extravagant, wholly good grace and gifts of God or with God their giver.

- Page 30: “The gifts of the Spirit may be controversial, but the gift of the Spirit is as unifying a doctrine as there is.”

- Page 49: “We find wine mentioned when people talk about the Lord’s Supper and when they talk about the filling with the Holy Spirit.” Page 50: “Sacraments fuel happiness.”

- Page 68: “If you want to be truly evangelical, be Eucharistic.”

His final point on spiritual gifts is that they were for anonymous (ordinary) Christians as well as the apostles; while their frequency decreased over time, documented evidence from the ante-Nicene Fathers shows that they did persist through at least the first 500 years of church history.

Thus, the Holiness stream has its place within Anglicanism. What are your thoughts on and experiences with this stream? Share in the comments below!

Comments

Post a Comment